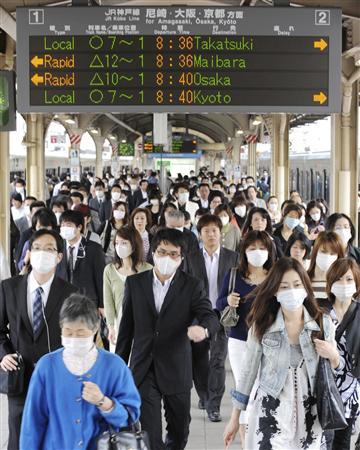

Japanese Face Masks Help Prevent the Spread of Coronavirus

Wearing masks for medical reasons is a long-established tradition in Japan

by Leroy W. Demery, Jr.

Special to California Rail News

The 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918-1919 resulted in an estimated 257,000 – 481,000 deaths in Japan. (A recent study based on prefectural-level records concluded that the death toll was much higher, 1.97 – 2.02 million.) The pandemic gave rise to a singular response in Japan: the wearing of masks to control the spread of airborne disease. (Face masks would probably have been introduced to Japan’s former external possessions, e.g. Taiwan and Korea, at the same time.)

In time, masks became part of Japanese social etiquette. Forty years ago, it was not uncommon to see people, suffering from colds, wearing reusable gauze masks to avoid spreading viruses to others. Today, “sickness mask culture” has expanded greatly – both in volume (annual sales) and uses – for health-related and non-health reasons.

Masks as protection became common during flu season, in particular during the H1N1 (“swine flu”) pandemic of 2009-10. Another occasion for wearing a mask for protection: taking children to the doctor. People who suffer from hay fever or other allergies often use masks during springtime to help reduce exposure to allergens.

Masks are popular for aesthetic reasons and as fashion statements. Some people believe that masks make their faces appear “smaller” (“small face” is considered a desirable feature in Japan) – and emphasize their eyes. Scented masks, odor-absorbing masks, colored masks (black masks are popular), form-fitting masks, masks marketed to women (e.g. with lotion), or men . . . and so forth.

Masks are said to provide a “privacy shield,” as sunglasses do. Some celebrities wear masks in public to avoid recognition. According to stereotype, criminals often wear masks and sunglasses to hide their identities. Some retail outlets post signs forbidding entry to persons wearing both masks and sunglasses, and police training exercises feature “robbers” who wear masks and sunglasses.

The Japanese word for “mask” is just that – “mask,” borrowed from English. This is spelled out in katakana phonetic characters as マスク. This, at slow speed, would be pronounced ma-su-ku but at normal conversational speed sounds much closer to the English pronunciation than implied by the katakana.

The popularity of masks increased dramatically from the early 2000s, when surgical-style disposable masks were first sold as consumer products. The initial marketing targeted people who suffer from pollen allergies, but the new masks quickly became the “standard,” displacing the reusable gauze masks used previously. The new masks are made from lightweight non-woven material, and are known for low cost, ease of use and disposability. (Littering of discarded masks has become a problem in Japan – at restaurants in particular.)

The sale of masks in Japan has soared over the past decade. According to the Japan Hygiene Products Industry Association, fewer than one billion masks were sold during 2010. By 2018, sales exceeded 5.5 billion at 2018. The great majority of these – 4.3 billion – were for personal use. About one billion were for medical use, and a small fraction – about 0.2 billion – for industrial use. The great majority of all masks (more than 4 billion) were imported from suppliers overseas.

The coronavirus pandemic has led to soaring demand for medical masks. This has generated concerns about the stability of the mask supply. Last month, a major domestic producer announced that it would sharply increase production of antibacterial masks. Another apparent result: price gouging. Masks have been offered online at greatly inflated prices, by unregulated outlets described as “online flea market sites.” This led to allegations that some individuals purchase masks at pharmacies and other retail outlets for resale online at large markups (e.g. 10 times retail price). In March, the government banned the resale of masks “at prices higher than acquisition prices.” This was described as part of government efforts to eliminate shortages of face masks as the COVID-19 virus spreads. The ban covers masks purchased at retail outlets and online, and does not apply to “business transactions” among suppliers, wholesalers and retailers.

Local governments, responding to concerns and complaints about mask shortages, have begun posting instructions on websites for residents to make their own face masks and disinfectants. In addition to Japanese, such instructions have been posted in English, Chinese and Korean, for the benefit of foreign visitors.

Demand for masks is likely to climb even higher: a government panel of experts warned at mid-March that, in spite of Japan’s success in “flattening the curve” of COVID-19 virus proliferation to some extent, the continued spread of the virus in some regions could lead to a “massive epidemic.”

Near the end of February, the government of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe requested emergency closures of all primary and secondary schools – elementary, junior high, high school and special needs – until the start of the scheduled spring break. This was part of the government’s measures to contain the virus. Implementation was left to municipalities and prefectures. Compliance was very high but not total (e.g. 98.8 percent of all municipal elementary schools started “extraordinary breaks” During March, Abe directed the education ministry to draft guidelines for school reopening.

As of 2020 March 18, Japan had 873 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 31 fatalities. The number of infections reported by local governments ranged from 1 (several prefectures) to 154 (Hokkaidō). On February 28, Governor Naomichi Suzuki declared a three-week state of emergency in Hokkaidō, the prefecture with the largest number of COVID-19 cases, including a weekend “stay at home” request and school closures. This ended as scheduled on March 19. An important aspect of the government response to regional outbreaks of COVID-19 in Japan is masks.

The reaction of foreign visitors to Japan’s mask culture has been stereotyped by various Japanese media outlets as steeped in skepticism and lack of comprehension. It is true that some foreign visitors say they do not understand the popularity of face masks, or describe mask culture as “strange,” “weird,” or other pejorative terms. However, it is also true that a small number of people, in countries far from Asia, could be seen wearing face masks well before 2020. In the US, the popularity of face masks among college students, during “flu season” in particular, grew significantly from 2000, and this growth accelerated rapidly following the “swine flu” pandemic of 2009-2010. Some of the people who wore face masks prior to 2020 were obviously not of Asian ancestry.

The effectiveness of masks in preventing the transmission of airborne viral disease has been questioned – or flatly denied, as by the US Surgeon General, Jerome M. Adams, MD, MPH, at the end of February. Outside the U.S., this was widely understood as an attempt to downplay the shortage of masks, a key part of the federal government’s fumbled response to the novel coronavirus. A recent study indicated there are 7 asymptomatic viral carriers for every identified case. To seriously reduce the rate of viral transmission, that makes it essential that the entire population wear masks when out in public. Americans should pay careful attention to the Japanese experience with face masks – attention which has been sorely lacking to date.

References:

Coronavirus: Why some countries wear masks and others don’t https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52015486?utm_source=pocket-newta

Thailand makes wearing masks mandatory on subway system and trains: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1885665/face-masks-compulsory-on-all-trains

Why are U.S. officials dismissive of protective face covering? https://www.scmp.com/news/world/united-states-canada/article/3077686/coronavirus-mask-mystery-why-are-us-officials

Chandra, Siddharth. 2013. Deaths Associated with Influenza Pandemic of 1918–19, Japan [Emerging Infectious Diseases] Journal, 19,4:616-622, April 2013. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/19/4/12-0103_article.

EID [Emerging Infectious Diseases] Journal, 19,4:616-622, April 2013. doi:10.3201/eid1904.120103.

Nippon.com. 2016. Mask Culture in Japan. 2016 February 11.

Ashcraft, Brian. 2018. Let’s Talk About Japan And Sickness Masks. Kotaku, 2019 May 9.

Nippon.com. 2020. Mask Prices Surge on Online Flea Markets amid Coronavirus Scares. 2020 February 3.

Nippon.com. 2020. Demand for Disposable Face Masks Pushes Japanese Production Above 4 Billion Annually. 2020 February 5.

Nippon.com. 2020. Japan Rushes to Supply Face Masks as Hospitals Worried. 2020 February 5.

Nippon.com. 2020. Sharp Increase in Mask Production. 2020 February 14.

Nippon.com. 2020. Japan Local Govts Teaching Residents about Making Face Masks. 2020 February 27.

Nippon.com. 2020. 98.8 Pct of Japan Elementary Schools Shut after Abe Request. 2020 March 4.

Nippon.com. 2020. Japan to Provide Hokkaido with 4 Million Masks. 2020 March 4.

Nippon.com. 2020. Japan to Ban Face Mask Resale at Higher Prices. 2020 March 10.

Nippon.com. 2020. Face Mask Littering Causing Headaches in Japan. 2020 March 17.

Tufekci, Zeynep. 2020. “Why Telling People They Don’t Need Masks Backfired.” NY Times, 2020 March 17.

Nippon.com. 2020. Hokkaido to End State of Emergency over Coronavirus Thurs. 2020 March 18.

Nippon.com. 2020. Coronavirus Cases by Country. 2020 March 19.

Nippon.com/ 2020. Coronavirus Cases in Japan by Prefecture. 2020 March 19.

Nippon.com. 2020. Japan Panel Warns of Risk of Massive Coronavirus Epidemic. 2020 March 20.

Nippon.com. 2020. Japan to Lift School Closure Request over Coronavirus in Stages. 2020 March 20.

Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus, https://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2020/03/24/science.abb3221